This chapter provides information about monitoring statistics with the xmperf program.

You can benefit from having xmperf working while you read this chapter. To do this, follow the instructions in Appendix A, Installing the Performance Toolbox for AIX to install the program and supporting files. When you have successfully installed the files, follow these steps:

Monitoring the performance of computer systems is one of the most important tasks of a system administrator. Performance monitoring is important for many reasons, including:

The xmperf performance monitor is a powerful and comprehensive graphical monitoring system. It is designed to monitor the performance on the system where it itself is executing and at the same time allow monitoring of remote systems via a network. Every host to be monitored by xmperf, including the system where xmperf runs, must have the Agent component installed and properly configured.

Note: Remote systems can only be monitored if the Performance Toolbox Network feature is installed. If the Performance Toolbox Local feature is installed then only the local host can be monitored. Discussions about remote system monitoring pertain only to the Performance Toolbox Network feature.

In addition to monitoring performance in semi-real time, xmperf also is designed to allow recording of performance data and to play recorded performance data back in graphical windows.

The xmperf program is the most comprehensive and largest program in the Manager component of PTX. It is an X Window System-based program developed with the OSF/Motif Toolkit. The xmperf program allows you to define monitoring environments to supervise the performance of the local AIX system and remote systems. Each monitoring environment consists of a number of consoles. Consoles show up as graphical windows on the display. Consoles, in turn, contain one or more instruments and each instrument can show one or more values that are monitored.

Each xmperf environment is kept in a separate configuration file. The configuration file defaults to the file name xmperf.cf in your home directory but a different file can be specified when xmperf is started. See Overview of File Placement for alternative locations of this file.

Consoles are named entities allowing you to activate any one or more consoles by selecting from a menu. New consoles can be defined and existing ones can be changed interactively. Consoles allow you to define and group collections of monitoring instruments in whichever configuration is convenient. Instruments are the actual monitoring devices enclosed within consoles as rectangular graphical subwindows.

Instruments come in two flavors:

All instruments are defined with a primary graph style. The following graph styles are currently available:

Recording graphs:

State graphs:

All instruments can monitor up to 24 different statistics at a time. Each statistic is represented by a value. Values can be selected from menus of available statistics. Depending on your system and the availability of tools, statistics could be local or remote.

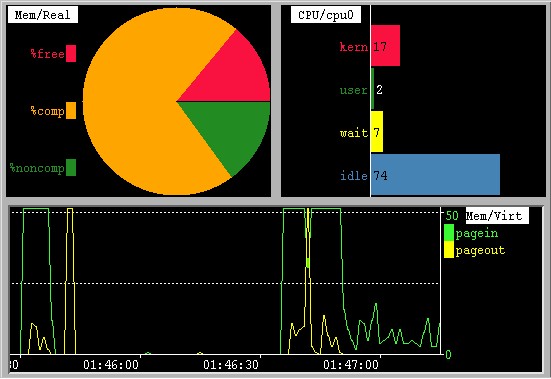

To illustrate these concepts, think of a hypothetical example (illustrated in the figure Sample xmperf Console) of a console defined to contain three instruments as follows:

State instrument, shaped as a pie chart, showing three values as a percentage of total memory in the local system:

Recording instrument, plotted as a state bar graph, showing four values:

Recording instrument, plotted as a line graph, showing:

Sample xmperf Console

In addition to the monitoring features, xmperf also provides an enhanced interface to system commands. You configure the interface by editing the xmperf configuration file. Commands can be grouped under either of three main menu items:

As another convenience to you, xmperf also can be used to display a list of active processes in the system. The list can be sorted after a number of criteria. Associated with the process list is yet another user-configurable command menu. Commands defined here take a list of process IDs as argument.

Whenever you start xmperf, you must supply a configuration file to define the environment in which you want to do the monitoring. The file may be an empty (zero-length) file, in which case you must define the environment from scratch. If no file is specified, xmperf defaults to the file xmperf.cf in your home directory. If the file does not exist in your home directory, it is searched for as described in Overview of File Placement. Normally, the configuration file defines one or more consoles, each typically used to monitor a related set of performance data. For example, one console might be called "Network" and provide one graph for each network interface in the system. Another might be called "Disks" and contain graphs to show the activity of each physical disk and the types of input/output requests.

The configuration file, thus, defines the environment and contains one or more definitions of consoles. Together they constitute the top two levels in the hierarchy. The third level is the subdivision of consoles into instruments. Using the "Network" example from above, this console might have an instrument defined for each of your system's network interfaces. This way, whenever you want to check the network load, you simply call a monitoring console by its name, in this case "Network," and monitoring starts immediately.

Returning to the example of network monitoring, obviously, there's more than one thing to keep an eye on for each of the network interfaces in a system. You might want to monitor the number of retransmissions and probably want to know how much network load comes from input and how much from output. Those are just a couple of the many types of data that might interest you. In xmperf terms, each data type is referred to as a value and represents a flow of data from one particular type of statistics collected by the system. If each of these data values had to be monitored in separate instruments, it would be difficult to correlate them and you'd end up with an unmanageable number of instruments for even simple monitoring tasks. Therefore, an instrument can be made to monitor more than one value so that each instrument monitors a set of data values. Values comprise the fourth level in the monitoring hierarchy.

A given system, at any point in time, has a number of system resources that do not change between boots. Such resources include, but are not limited to, the following:

Your system collects a large amount of performance-related statistics about such resources. This data can be accessed from application programs through the APIs provided by PTX. One such application program is xmperf. It provides a user interface that allows you to select the data to monitor from lists of the data available. By selecting multiple data values, you can build instruments where multiple statistics can be plotted on a common time scale for easy correlation.

When you select a value to monitor, you get a set of default properties for that data value. Each property can be changed to reflect special needs. The properties associated with a data value and their defaults are as follows:

| Style | A secondary graph style, which is ignored for state

graphs. By specifying a secondary graph style

different from the primary style of an instrument,

interesting effects can be created. For example, if

the instrument's primary style is a bar graph, then

you can choose a line graph style for one or more

values to plot related values so they overlay the bar

graph.

Default = Same as primary style for instrument. |

| Color | The color used to represent the value when plotted.

If the value is displayed as a state light, the color

is used to paint the "lights" when a data

value is lower than a descending threshold or higher

than an ascending threshold.

Default = As specified in resource file (see The xmperf Resource File) or (for colors not defined in resource file) generated from colors in the color map and contrasting from neighbor colors. |

| Tile | A pattern (pixmap) used to "tile" the value

as it is drawn in an instrument. Tiles are ignored

for line drawing, for text, and for the state light

type instruments. When tiling is used, it is always

done by mixing the color of the value and the

background color of the instrument in one out of

eleven available patterns, numbered from 1 to 11.

Default = foreground (tile 1 = 100% foreground color). |

| Scale, low | The lowest value plotted. This property only has a

meaning for recording graphs and for the state bar

graph.

When a low scale value is given for a recording graph or a state bar graph, then the scale of the graph goes from the low scale value to the high scale value. For example, if the low scale is 50 and high scale is 100, then the lowest value you will ever see plotted in the instrument is 51. A value of 75 would extend half-way into the plotting area. Default = From system tables, usually zero. |

| Scale, high | The value that determines the scale of the graphs. If

values are encountered that exceed the high scale

limit, the graphs are cut off to fit the plotting

area. This property has no meaning for the state

light graph type.

Default = From system tables. |

| Threshold | This property is used only for the state light graph

type. It defines the value at which the "light

is turned on." Whether the light is on when the

value is above or below the threshold is determined

by the threshold type.

Default = zero. |

| Threshold Type | This property is used only for the state light graph

type. It must be descending or ascending. If

descending, the light is turned on when the last

value received is equal to or below the threshold. If

ascending, the light is turned on when the last value

received is equal to or above the threshold.

Default = Ascending. |

| Label | This property can be used to specify a user-defined

text that is used to label the value in the

instrument.

Default = Null (path name of value is used, see Path Names). |

Many system resources exist in multiple copies. For example, a system may have three disks, and two of those may be used for paging space. A system may also have multiple network interfaces, and several other resources may be duplicated. Generally, one set of statistics is collected for each resource copy.

Because of this duplication of statistics, the selection of values to plot in an instrument is done through a multi-level selection process. Since this process is available, it is also used to group statistics even when they are not duplicated. The unique name used to identify a value is composed of one-level names separated by slashes, much like a fully qualified UNIX file name. The fully qualified name of a value is called the path name of the value. To identify the percentage of time a particular disk on the host system with the hostname birte is busy, the path name might be:

hosts/birte/Disk/hdisk02/busy

For space reasons, it is seldom possible to display all of the path name in instruments. For example, given that the number of characters used to display value names is 12, only the last 12 characters of the above name would be displayed, yielding:

hdisk02/busy

The default length of a value name is 12, but you can specify up to 32 characters using the command line argument -w. In addition, the -a command line argument allows you to request adjustment of the text length to what is necessary to display the value names. When -a is used, the text length may be less than what is specified by -w (or the default, whichever applies) but never longer. The X Window System resources LegendAdjust and LegendWidth can be used in place of the command line arguments. See The xmperf Command Line for a description of command line options and The xmperf Resource File for a description of supported resources.

In many cases, an instrument or a console is used to display statistics that have some of the value path name in common. When this happens, xmperf automatically removes the common part of the name from the displayed name and shows it in an appropriate place, dependent on the type of instruments used. This is explained in Value Name Display and The Console Title Bar.

No matter how much thought is put into the naming of each level in the hierarchy of statistics, you are bound to end up with some that are not very informative. In such cases you might want to specify your own name for a value. You can do so from the dialog box used to add or change a value as described in Changing the Properties of a Value.

An instrument occupies a rectangular area within the window that represents a console. Each instrument may plot up to 24 values simultaneously. The instrument defines a set of statistics and is fed by network packets that contain a reading of all the values in the set, taken at the same time. All values in an instrument must be supplied from the same host system.

The instrument shows the incoming observations of the values as they are received depending on the type of statistic selected. Statistics can be of types:

Instruments defined in xmperf correspond to statsets in the xmservd daemons of the systems the instruments are monitoring. The section on Statsets gives information about statsets and their relationship to instruments.

Instruments can be configured through a menu-based interface as described in The Modify Instrument Submenu. In addition to selecting from 1 to 24 values to be monitored by the instrument, the following properties are established for the instrument as a whole:

| Style | The primary graph style of the instrument. If the

graph is a recording graph, not all values plotted by

the graph need to use this graph style. In the case

of state graphs, all values are forced to use the

primary style of the instrument.

Default = Line graph. |

| Foreground | The foreground color of the instrument. Most

noticeably used to display time stamps and lines to

define the graph limits. Default = White. |

| Background | The background color of the instrument.

Default = Black. |

| Tile | A pattern (pixmap) used to "tile" the

background of the instrument. Tiles are ignored for

state light type instruments. When tiling is used, it

is always done by mixing the foreground color and the

background color of the instrument in one out of

eleven available patterns. Default = Tile 2 (100% background color, that is, no tiling). |

| Interval | The time interval between observations. Minimum is

0.2 second, maximum is 30 minutes. Even though the

sampling interval can be requested as any value in

the above range, it may be changed by the xmservd

daemon on the remote system that supplies the

statistics. For example, if you request a sampling

interval of 0.2 second but the remote host's daemon

is configured to send data no faster than every 500

milliseconds, then the remote host determines the

speed. As explained in Rounding of Sampling Interval, xmservd rounds

sampling intervals so that the example above would

result in an effective sampling interval of 500

milliseconds.

Default = 5 seconds. |

| History | The number of observations to be maintained by the

instrument. For example, if the interval between

observations is 5 seconds and you have specified that

the history is 1,000 readings, then the time period

covered by the graph is 1,000 x 5 seconds or

approximately 83 minutes. The history property has a meaning for recording graphs only. If the current size of the instrument is too small to show the entire time period defined by the history property you can scroll the instrument to look at older values. State graphs show only the latest reading so the history property does not have a meaning for those. However, since you can change the primary style of an instrument at any time, the actual readings of data values are still kept according to the history property. This means that data is not lost if you change the primary style from a state graph to a recording graph. The minimum number of observations is 50 and the maximum number you can specify is 5,000. Default = 500 readings. |

| Stacking | The concept of stacking allows you to have data

values plotted "on top of" each other.

Stacking works only for values that use the primary

style. To illustrate, think of a bar graph where the

kernel-CPU and user-CPU time are plotted as stacked.

If at one point in time the kernel-CPU is 15% and the

user-CPU is 40%, then the corresponding bar goes from

0-15% in the color of kernel-CPU, and from 16-55% in

the color used to draw user-CPU. If you wanted to overlay this graph with the number of page-in requests, you could do so by letting this value use the skyline graph style, for example. It is important to know that values are plotted in the sequence they are defined. Thus, if you wanted to switch the CPU measurements above, simply define user-CPU before you define kernel-CPU. Values to overlay graphs in a different style should always be defined last so as not to be obscured by the primary style graphs. Default = No stacking. |

| Shifting | This property is meaningful for recording graphs

only. It determines the number of pixels the graph

should move as each reading of values is received.

The size of this property has a dramatic influence on

the amount of memory used to display the graph since

the size of the pixmap (image) of the graph is

proportional with the product:

history x shifting x graph height If the shifting is set to one pixel, a line graph looks the same as a skyline graph, and an area graph looks the same as a bar graph. Maximum shifting is 20 pixels, minimum is (spacing + 1) pixel. Default = 4 pixels. |

| Spacing | A property used only for bar graphs and state bar

graphs. It defines the number of pixels separating

the bar of one reading from the bar of the next. For

a bar graph, the width of a bar is always (shifting

-- spacing) pixels. The property must always be from

zero to one less than the number of pixels to shift.

Default = 2 pixels. |

In addition to the above properties that can be modified through a menu interface, four properties determine the relative position of an instrument within a console. They describe, as a percentage of the console's width and height, where the top, bottom, left and right sides of the instrument are located. In this way, the size of an instrument is defined as a percentage of the size of the monitor window.

The relative position of the instrument can be modified by moving and resizing it as described in Moving Instruments in a Console and Resizing Instruments in a Console.

For the state light graph type, foreground and background colors are used in a special way. To understand this, consider that state lights are shown as text labels "stuck" onto a background window area like you would stick paper notes to a bulletin board. The background window area is painted with the foreground color of the instrument rather than with the background color. The color of the background window area never changes.

Each state light may be in one of two states: lit (on) or dark (off). When the light is "off," the value is shown with the label background in the instrument's background color and the text in the instrument's foreground color. Notice, that if the instrument's foreground and background colors are the same, you see only an instrument painted with this color; no text or label outline is visible. If the two instrument colors are different, the labels are seen against the instrument background and label texts are visible.

When the light is on, the instrument's background color is used to paint the text while the value color is used to paint the label background. This special use of colors for state lights allows for the definition of alarms that are invisible when not triggered or alarms that are always visible.

Some statistics change over time. The most prominent example of statistics that change is the set of processes running on a system. Because process numbers are assigned by the operating system as new processes are started, you can never know what process number an execution of a program will be assigned. Clearly, this makes it difficult to define consoles and instruments in the configuration file.

To help you cope with this situation, a special form of consoles can be used to define skeleton instruments. Skeleton instruments are defined as having a "wildcard" in place of one of the hierarchical levels in the path that defines a value. For example, you could specify that a skeleton instrument has the following two values defined:

Proc/*/kern Proc/*/user

The wildcard is represented by the asterisk. It appears in the place where a fully qualified path name would have a process ID. Whenever you try to start a console with such a wildcard, you are presented with a list of processes. From this list, you can select one or more instances. To select more than one instance, move the mouse pointer to the first instance you want, then press the left mouse button and move the mouse while holding the button down. When all instances you want are selected, release the mouse button. If you want to select instances that are not adjacent in the list, press and hold the Ctrl key on the keyboard while you make your selection. When all instances are selected, release the Ctrl key.

Skeleton consoles can not be defined through the menu interface. They must be defined by entering the skeleton console definitions in the xmperf configuration file. This is described in Defining Skeleton Consoles.

Each process selected is used to generate a fully qualified path name. If the wildcard represents a context other than the process context, such as disks, remote hosts, or LAN interfaces, the selection list will represent the instances of that other context. In either case, the selection you make is used to generate a list of fully qualified path names. Each path name is then used to define a value to be plotted or to define a new instrument in the console. Whether you get one or the other, depends on the type of skeleton you defined. There are two types of skeleton consoles:

Instantiated Skeleton Console

The skeleton type named "All" includes all value instances you select into the instrument. A skeleton instrument creates exactly one instance of an instrument and this single instrument contains values for all selected value instances. This is shown in the right side of the instantiated skeleton console shown in the preceding figure, Instantiated Skeleton Console. Two type "All" instruments are defined in the right side of the console and three processes were selected to instantiate the skeleton console.

Skeleton instruments of type "All" are defined with only one value because the instantiated instrument contains one value for each of the selections you make from the instance list.

Consoles can be defined with both skeleton instrument types but any non-skeleton instrument in the same console is ignored. The relative placement of the defined instruments is kept unchanged. When many value instances are selected, it can result in crowded instruments; but you can resolve this by resizing the console. When all the skeleton instruments in a console are type "All" skeletons, xmperf does not automatically resize the console.

The type of instrument best suited for the type "All" skeleton instruments is the state bar, but other graph types may be useful if you allow colors to be assigned to the values automatically. To do the latter, specify the color as default when you define the skeleton instrument.

This skeleton type is so named because each value instance you select creates one instance of the instrument. When you select five value instances, each of the type "Each" skeletons generates five instruments, one for each value instance. This is shown in the left side of the instantiated skeleton console shown in the Instantiated Skeleton Console. One type "Each" instrument is defined in the left side of the console and three processes were selected to instantiate the skeleton console.

Again, one console may define more than one skeleton instrument and you can define consoles with both skeleton instrument types while any non-skeleton instruments in the same console are ignored. The relative placement of the defined instrument is kept unchanged. This may give you very small instruments when many value instances are selected, but it's easy to resize the console. If the generated instruments would otherwise become too small, xmperf attempts to resize the entire console.

The types of instruments best suited for the "Each" type skeleton instruments are the recording instruments. This is further emphasized by the way instruments are created from the skeleton:

Wildcards must represent a section of a value path name which is not the end point of the path. It could represent any other part of the path, but it only makes sense if that part may vary from time to time or between systems. Currently, the following wildcards make sense:

CPU/*/... Processing units Disk/*/... Physical disks FS/rootvg/*/... File systems IP/NetIF/*/... IP interfaces LAN/*/... Network (LAN) interfaces PagSp/*/... Page spaces Proc/*/... Processes hosts/*/... Remote hosts Mem/Kmem/*/... Kernel Memory Allocations RTime/ARM/xaction/*/... ARM response time and activity RTime/LAN/*/... IP response time

Note: Not all wildcards are available on non-RS/6000 systems.

The file systems wildcard is one of the two current example of path names where more than one wildcard would be appropriate. It is not uncommon for a system to have more than one volume group defined, in which case you need to define an instrument for each volume group, as follows:

FS/rootvg/*/... Root volume group FS/myvg/*/... Private volume group FS/yourvg/*/... Another private volume group

The other example is that of ARM response time metrics where the higher level of wildcard is the application identifier and the lower is the transaction identifier.

The xmperf program does not allow you to specify multiple wildcards in a skeleton instrument. However, it is possible to use dual wildcards in the 3dmon program as described in 3D Monitor.

When a console contains skeleton instruments, all such instruments must use the same wildcard. Mixing wildcards would complicate the selection process beyond the reasonable and the resulting graphical display would be incomprehensible.

When all values in an instrument have all or part of the value path name in common, xmperf removes the common part of the name from the value names displayed in the instrument and displays the common part in a suitable place. To determine how to do this, xmperf examines the names of all values in the containing console.

To illustrate, assume we have a single instrument in a console, and that this instrument contains the values:

hosts/birte/PagSp/paging00/%free hosts/birte/PagSp/hd6/%free

Names are checked as follows:

<hosts/birte/PagSp/>

The parts of the value names left to be displayed in the instrument are:

paging00/%free hd6/%free

paging00 hd6

The common part of the value name (without the separating slash) is displayed within the instrument in reverse video, using the background and foreground colors of the instrument. The actual place used to display the common part depends on the primary graph type of the instrument.

An example of this way to display value path names is shown in the figure Instantiated Skeleton Console, where the center instrument on the left contains the values:

hosts/nchris/Proc/4569~xmservd/kerncpu hosts/nchris/Proc/4569~xmservd/usercpu hosts/nchris/Proc/4569~xmservd/nsignals

The process number (4569) is not shown in the instrument because the instrument was configured to only show the name of the executing program.

If the beginning of the value names in an instrument (after having been truncated using the checking described in step 1) have a common part, this string is removed from the value path names and displayed in reverse video within the instrument.

To illustrate, assume we have a console with two instruments. The first instrument has the values:

hosts/umbra/Mem/Virt/pagein hosts/umbra/Mem/Virt/pageout

while the second instrument has:

hosts/umbra/Mem/Real/%comp hosts/umbra/Mem/Real/%free

The result of applying the three rules to detect common parts of the value names would cause the title bar of the console window to display <hosts/umbra/Mem/>. The first instrument would then have the text Virt displayed in reverse video and the value names reduced to:

pagein pageout

The second instrument would display Real in reverse video and use the value names:

%comp %free

An example of the above can be seen in the Sample xmperf Console figure. The console shown in the figure has three instruments and the values for each instrument come from the same contexts. The path names of the three instruments (clockwise from the top left) are:

hosts/nchris/Mem/Real/%free hosts/nchris/Mem/Real/%comp hosts/nchris/Mem/Real/%noncomp hosts/nchris/CPU/cpu0/kern hosts/nchris/CPU/cpu0/user hosts/nchris/CPU/cpu0/wait hosts/nchris/CPU/cpu0/idle hosts/nchris/Mem/Virt/pagein hosts/nchris/Mem/Virt/pageout

Certain operations you can perform on an xmperf instrument, even legal operations, can produce surprising results. Here are a few of the things that may surprise you:

Similarly, secondary style information can be lost if you change from one recording graph style to another. For example, assume an instrument has a primary style of bar graph, three values using this primary style, and a single value using a secondary style, which is line graph. If you change this instrument's primary style to be line graph, then you lose the information about secondary style. Had you changed the primary style to skyline, then the secondary style would be remembered.

If the product (history x shift) is too large, the graph is distorted. The only way you can currently change that is to reduce one or both properties.

Don't let this bother you; simply grab the palette window and move it to the side.To move the palette window out of the way, click the mouse button on the title menu bar of the palette window and hold the button down as you reposition the window.

Notice that as you choose a color, the instrument is changed immediately. This allows you to experiment with colors without making permanent changes to the instrument. When you have selected the color you want, click on the Proceed button to make the change permanent.

Some common wildcards are those represented by physical or logical disks, page space on disks, network interfaces, processes, and remote hosts.

Ghost instruments occupy the space and prevent you from defining a new instrument in that same space and moving or resizing other instruments to use the space. While this is inconvenient, it serves the purpose of maintaining the console definition intact if you modify other parts of the console. Ghost instruments can not be removed except by editing the xmperf configuration file.

Consoles, like instruments, are rectangular areas on a graphical display. They are created in top-level windows of the OSF/Motif ApplicationShell class, which means that if you use the mwm window manager, each console has full OSF/Motif window manager decorations. These window decorations allow you to use the mwm window manager functions to resize, move, minimize, maximize, and close the console.

Consoles are useful for managing instruments:

Consoles can contain non-skeleton instruments or skeleton instruments but not both. Consequently, it makes sense to classify consoles as either non-skeleton or skeleton consoles.

Non-skeleton consoles can be in either an opened or closed state. You open a console by selecting it from the Monitor menu. Once the console has been opened, it can be minimized, moved, maximized, and resized using mwm. None of these actions change the status of the console. You might not see the console on the display, but it is still considered open and if recording has been started, it continues.

If you look at the Monitor menu after you have opened one or more non-skeleton consoles, the name of the console is now preceded by an asterisk. This indicates that the console is open. If you click on one of the names preceded by an asterisk, you close the corresponding console.

Skeleton consoles themselves can never be opened. When you select one from the Monitor menu, you are presented with a list of names matching the wildcard in the value names for the instruments in the skeleton console. If you select one or more from this list, a new non-skeleton console is created and added to the Monitor menu. This new non-skeleton console is automatically opened, and given a name constructed from the skeleton console name suffixed with a sequence number.

The non-skeleton console created from the skeleton is said to be an "instance" of the skeleton console; we say that a non-skeleton console has been instantiated from the skeleton. The instantiated non-skeleton console works exactly as any other non-skeleton console, except that changes you make to it never affect the configuration file. You can close the new console and reopen it as often as you wish, and you can resize, move, minimize, and maximize it.

Each time you select a skeleton console from the Monitor menu you get a new instantiation, each one with a unique name. For each instantiation you'll be prompted to select values for the wildcard, so each instantiation can be different from all others.

If you have created an instance of a skeleton console and you'd like to change it into a non-skeleton console and save it in the configuration file, the easiest way to do so is to choose Copy Console from the Console menu. This prompts you for a name of the new console and the copy is a non-skeleton console that looks exactly like the instantiated skeleton console from which you copied. Once you have copied the console, you can delete the instantiated skeleton console and save the changes in the configuration file.

Within their enclosing ApplicationShell windows, all consoles are defined as OSF/Motif widgets of the XmForm class and the placement of instruments within this container widget is done as relative positioning. Relative positioning has advantages and disadvantages. One advantage is the easy resizing of a console without loss of relative positions of the enclosed instruments. A disadvantage is the complexity involved when adding or removing an instrument in an already full console.

When you want to add an instrument to a console, you can choose between adding a new instrument or copying one that's already in the console. If you choose to create a new instrument, the following happens:

If you choose to copy an existing instrument, the following happens:

Rounding may cause the height of the new instrument to deviate 1-2 percent from the intended height.

Once you've selected an instrument and chosen to resize it, the instrument goes away and is replaced by a rubber-band outline of the instrument. You resize the instrument by holding mouse button 1 down and moving the mouse. When you press the button the pointer is moved to the lower right corner of the outline and resizing is always done by moving this corner while the upper left corner of the outline stays where it is.

During resizing, a small button is shown in the top left corner of the rubberband outline. It shows the calculated relative size of the instrument as width x height in percent of the console's total width and height. The relative size is calculated from the relative positions of the edges of the instrument as:

For example, for an instrument to have a width of 49 and a height of 20, the edges might have the following relative positions:

When you release the mouse button the instrument is redrawn in its new size.

Note that it's normally a good idea to move the instrument within the console so that the upper left corner is at the desired position before resizing.

The position of the resized instrument must be rounded so that it can be expressed in percentage of the console size. This can cause the instrument to change size slightly from what the rubber-band outline showed.

Instruments can not be resized so they overlap other instruments. If this is attempted, the size is reduced so as to eliminate the overlap.

When you select an instrument to be moved, the instrument disappears and is replaced by a rubber-band outline of the instrument. To begin moving the instrument, place the mouse cursor within the outline and press the left mouse button. Hold the button down while moving the mouse until the outline is where you want it, then release the button to redraw the instrument.

During moving, a small button is shown in the bottom right corner of the rubberband outline. It shows the calculated relative position of the top left corner of the instrument. This helps in positioning the instrument so that it aligns with the other instruments in the console.

Instruments can be moved over other instruments, but are not allowed to overlap them when the mouse button is released. If an overlap would occur, the instrument is truncated to eliminate the overlap.

The title bar of a console window contains three pieces of information. It might look like this, for example:

birte: Virtual Memory <hosts/xtra/Mem/Virt/>

The first two pieces of information are always present. The third part is only displayed if all statistics displayed in the console's instruments have some or all of the beginning of their value names in common. The three parts of the title bar text are:

Disks_#01

where the name of the skeleton console would then be Disks and the remainder is added to give the instantiated skeleton console a unique name.

When values are added to or removed from the console, the common part of the value names might change. When this happens, the console title bar changes to reflect this.

Environments are defined in configuration files. By default, xmperf reads its environment from the file $HOME/xmperf.cf or, if that file does not exist, then as described in Overview of File Placement. You can override the file name through the command line argument -o or the X Window System resource ConfigFile. Command line arguments are described in The xmperf Command Line and supported resources in The xmperf Resource File section.

In most situations, any one person should be able to stick to a single environment, defining all the consoles required for the monitoring that person needs. However, since the environment holds not only console definitions but also command definitions as described in The xmperf Command Menu Interface, different environments can be defined for different kinds of users. Most of all, this is a matter of what privilege is required to execute the commands.

A system administrator may be authorized to run commands such as renice and other commands that require root authority. Therefore, the system administrator may want to have more commands or different ones. When xmperf uses such environments, it can be necessary to start the program while logged in as root.

Note: This function is only available with the Performance Toolbox Network feature. If you try to access these functions with the Performance Toolbox Local feature only the local hostname is displayed for selection.

Visualizing the load statistics (or monitoring the performance) of a single local host on that same host has been done with a great variety of tools, developed over many years. The tools can be useful for critical hosts such as database servers and file servers, provided you can get access to the host and that the host has capacity to run the tool.

Some of the existing tools, especially when based on the X Window System, allow the actual display of output to take place on another host. Even so, most existing tools depend on the full monitoring program to run on the host to be monitored, no matter where the output is shown. This induces an overhead from the monitoring program on the host to be monitored.

Performance Toolbox for AIX introduces true remote monitoring by reducing the executable program on the system to be monitored to the Agent component's xmservd program, which consists of a data retrieval part and a network interface. It is implemented as a daemon that is started by the inetd super-daemon when requests from data consumers are received. The xmservd program is described in Monitoring Remote Systems.

The obvious advantage of using a daemon is that it minimizes the impact of the monitoring software on the system to be monitored and reduces the amount of network traffic. Because one host can monitor many remote hosts, larger installations may want to use dedicated hosts to monitor many or all other hosts in a network.

The responsibility for supplying data is separated from that of consuming data. Therefore, we have adopted the term data-supplier host to describe a host that supplies statistics to another host, while a host receiving, processing, and displaying the statistics is called a data-consumer host.

All data-consumer programs made to the RSi API (see Remote Statistics Interface Programming Guide), such as xmperf, are always doing remote monitoring in the sense that they can get their flow of statistics only from data supplier daemons. It is immaterial to the protocol, as to the programs, whether the daemon feeding a particular instrument runs on the local or a remote host.

It is, however, convenient that you can create and maintain consoles for the local host. The term Localhost refers to the host that all instruments in the xmperf configuration file are assumed to refer to when no hostname is given as part of their value path names.

The Localhost defaults to the host where xmperf is executing. Any other host can be selected at the time you start xmperf, using the command line argument -h. The Localhost can not be changed while xmperf is running.

Note: A change of Localhost has no influence on where commands, defined in the main window pulldown menus, are executed. Commands are always executed on the host where xmperf runs.

The xmperf program attempts to contact potential suppliers of remote statistics in the following situations:

The five-minute limit is implemented to make sure that the data-consumer host has an updated list of potential data-supplier hosts. Please note that this is not an unconditional broadcast every five minutes. Rather, the attempt to identify data-supplier hosts is restricted to times where a user wants to initiate remote monitoring and more than five minutes have elapsed since this was last done.

The five-minute limit not only gets information about potential data-supplier hosts that have recently started; it also removes from the list of data suppliers such hosts, which are no longer available. In heavily loaded networks and situations where one or more remote hosts are too busy to respond to invitations immediately, the refresh process may remove hosts from the list even though they do in fact run the xmservd daemon. If this happens, you should use the -r command line argument when you invoke xmperf. Through this option, you can increase the time xmperf waits for remote hosts to respond to invitations.

Once xmperf is aware of the need to identify potential data-supplier hosts, it uses one or more of the following methods to obtain the network address for sending an invitational are_you_there message. For a full description of network packet types and the network protocol see The xmquery Network Protocol. The last two methods depend on the presence of the file $HOME/Rsi.hosts. See Overview of File Placement for alternative locations of the Rsi.hosts file. The three ways to invite data-supplier hosts are:

The file $HOME/Rsi.hosts has a very simple layout. Only one keyword is recognized and only if placed in column one of a line. That keyword is:

nobroadcast

and means that the are_you_there message should not be broadcast using method 1 (where an invitation is sent to the broadcast address of each network interface on the host). This keyword is useful in situations where there is a large number of hosts on the network and only a well-defined subset should be remotely monitored. To say that you don't want broadcasts but want direct contact to three hosts, your $HOME/Rsi.hosts file might look like this:

nobroadcast birte.austin.ibm.com gatea.almaden.ibm.com umbra

The previous example shows that the hosts to monitor do not necessarily have to be in the same domain or on a local network. However, doing remote monitoring across a low-speed communications line is not likely to make you popular with other users of that communication line.

Be aware that whenever you want to monitor remote hosts that are not on the same subnet as the data-consumer host, you must specify the broadcast address of the other subnets or all the host names of those hosts in the $HOME/Rsi.hosts file. The reason is that IP broadcasts do not propagate through IP routers or gateways.

Note: Other routers can be configured to disallow UDP broadcast between subnets. If your routers disallow UDP broadcasts, enter the Internet address or hostname of all the hosts you want to monitor on other subnets in the $HOME/Rsi.hosts file.

The following example illustrates a situation where you want to do broadcasting on all local interfaces, want to broadcast on the subnet identified by the broadcast address 129.49.143.255, and also want to invite the host called umbra.

129.49.143.255 umbra

Note: The subnet mask corresponding to the broadcast address in this example is 255.255.240.0 and the range of addresses covered by the broadcast address is 129.49.128.0 through 129.49.143.255.

One of the message types passing between dynamic data-supplier and data-consumer hosts has a field that is used to tell the responding xmservd daemons whether any exception notifications (actually network packets of type except_rec) they may generate should be sent to the data-consumer host. Application programs control this field through the last argument to the RSiOpen and RSiInvite subroutine calls of the Remote Statistics Interface API. By default, the xmperf program does not request exception messages to be sent to it. This can be controlled through the command line argument -x or the X resource GetExceptions. Exception messages are used to inform about abnormal conditions detected on a system. They are described in the Handling Exceptions. When xmperf receives an exception message, it is displayed in the xmperf main window. No other action is taken. A better way of monitoring exceptions is provided by the program exmon described in the Monitoring Exceptions with exmon.

Two of the three main window menus that are used to define command menus have a fixed menu item. Those main window menus are Controls and Utilities. This section describes the Remote Processes fixed menu item in the Utilities pulldown menu. The purpose of the Remote Processes menu item is to provide you with an easy way to display the CPU-intensive processes on a remote host, which runs the xmservd daemon.

If you are monitoring remote systems you'll recognize the need for this function. It is not uncommon that a console used to monitor a remote host suddenly shows that something unexpected or unusual is happening on the host. To see what causes this, you would need to look into the processes that run on the remote host. However, it takes time to do a remote login and may even be impossible for certain types of errors or certain types of loads. This menu allows you to list key data for all processes running on the remote host without the need to do a remote login.

The first thing that happens when you select Remote Processes is that you see a list of remote hosts from which to select. An example of such a selection list is shown in the following figure, Host Selection List from xmperf.

Host Selection List from xmperf

When you select a host to monitor from Remote Processes, you immediately see a list of running processes in the remote host at the time you made the selection. It depends on the currently active display option (see Remote Processes Menu for details of how to set this option) of the remote process list whether all the processes of the remote host are shown, or whether only CPU-active processes are included. The list shows the most interesting details about the processes, and is sorted in descending order according to the CPU percentage used by the process. An example of a remote process list is shown in the following figure, Remote Process List from xmperf.

Remote Process List from xmperf

The fields in the list are, from left to right:

When the process overview list is displayed, a menu bar is available to control the list. The following menu items are available: